A Bay Area researcher on Saturday received science’s equivalent of a Hollywood Oscar for a surprising, transformative discovery about multiple sclerosis that offers hope of freeing those with the chronic illness from its debilitating effects.

UC San Francisco neurology professor Dr. Stephen Hauser, who shared with a Harvard professor a $3 million Breakthrough Prize for his research into MS and development of a pioneering treatment, “overturned the scientific consensus on the mechanism of MS,” and was instrumental in revolutionizing doctors’ approach to the common disease, a spokesperson for the award said.

Hauser’s discovery about MS, a neurological disease affecting nearly a million Americans, came on a ferry trip in British Columbia after he worked for decades to untangle the causes of MS and find possible treatments.

“When I first started — 47 years ago now — this quest to understand and successfully treat MS, the outlook for patients whose MS was beginning was severe disability within 15 years, or worse,” Hauser said. “For patients who are beginning their MS journey now, I think they can be optimistic that a life free from disability is achievable.”

On that 1997 ferry ride from Vancouver to Vancouver Island, a remark from a colleague led Hauser to laboratory investigations that upended scientists’ belief that T-type white blood cells wrought most of the neurological damage from MS. On the ship headed toward a meeting in B.C.’s capital Victoria, Claude Genain, a postdoctoral researcher in Hauser’s lab, suggested that perhaps B-type white cells were the main culprit. Hauser’s confirmation led to a pioneering treatment using a drug to kill B cells.

The drug therapy blocks nearly all of the bursts of inflammation that cause attacks of MS, so after a few years of treatment, if started early enough, “patients have on average less than one attack of MS per lifetime,” Hauser said. “Relapsing MS is really in the rearview mirror.”

However, researchers have found that a slow neurological degeneration occurs in the disease, partially independent of inflammation. The antibody-based drug slows that process about 40% in early MS cases, and about 30% in later stages, Hauser said. “We’re hopeful that if we can treat very, very early it may stop it entirely,” he said.

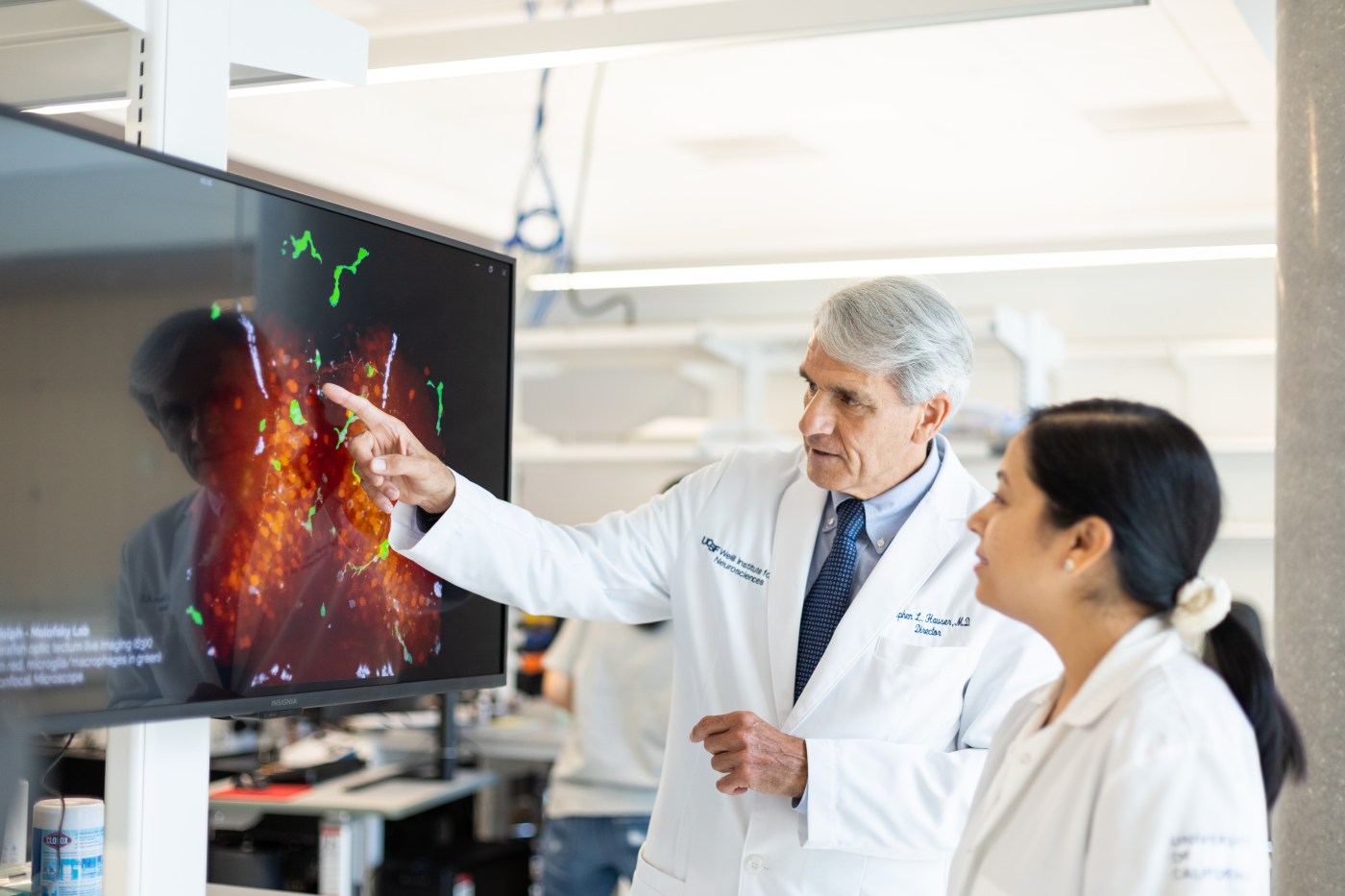

UC San Francisco professor and Weill Institute director Dr. Stephen Hauser works in his lab alongside postdoctoral researcher Chaitrali Saha (courtesy of UC San Francisco)

Hauser, director of UCSF’s Weill Institute for Neurosciences, received his Breakthrough Prize just as the U.S. National Institutes for Health — a primary funder of his work for decades — faces billions of dollars in cuts and the firing of more than 1,000 leaders and staff as Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency works to dramatically slash government spending and programs. A federal court lawsuit filed this week in Massachusetts by the American Public Health Association and others accused the federal government of a “reckless and illegal purge” that has seen hundreds of NIH-funded research projects “abruptly cancelled.” Musk in a February social media post called the amount universities spend to administer NIH grants “a ripoff.”

At the Weill Institute, which has received $1 billion in NIH funding since opening in 2016, Hauser and his team are probing connections between viruses and migraine, Lou Gehrig’s disease and Parkinson’s, to come up with new treatments. They are also studying novel ways to combat depression, autism, Alzheimer’s disease, psychosis, addiction and stroke, as well as improving the treatments for MS.

“This is going to be the golden age for medicine in the next generation and sooner if we’re able to keep on course,” Hauser said. “It’s an ecosystem that’s fragile and if any piece of it weakens then the gears can come apart.”

Related Articles

Letters: Scandal-plagued insurance commissioner must resign

One injured in fire Wednesday at Martinez Refining Company

Alzheimer’s disease study: researchers create at-home smell test for early detection

Death of veteran found in car at California VA hospital latest in string of suicides

Santa Clara County officially takes over operations of Regional Medical Center

Hauser frets that amid the Trump administration targeting of the NIH, young scientists may turn away from medical research, knee-capping health care progress for decades to come.

“I’m feeling worried about young people who are just beginning careers in medical science and are getting phone calls every week enticing them to do other things at far higher salaries,” Hauser said. “That could have generational consequences.”

Sharing the life-sciences Breakthrough Prize with Hauser was Harvard University professor Alberto Ascherio, who discovered that infection with the widespread Epstein-Barr virus was necessary for getting MS. Ascherio’s work “opens the possibility of treating MS with antiviral drugs” and development of a vaccine against Epstein-Barr that could prevent MS, said the Breakthrough Prize spokesperson. The high-profile science-award program was founded by Silicon Valley luminaries including Google co-founder Sergey Brin, and pediatrician and philanthropist Priscilla Chan and her husband, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg.

Four other Bay Area researchers took home related awards under the Breakthrough Prize umbrella.

Stanford University associate professor Jeongwan Haah won one of three New Horizons in Physics prizes, for his work at the intersection of math and quantum physics.

Rebecca Jensen-Clem, UC Santa Cruz assistant professor of astronomy and astrophysics, shared a New Horizons in Physics award with two other researchers, for demonstrating new techniques for finding tiny planets far outside our solar system.

Another Stanford faculty member, assistant math professor Si-Ying Lee, won one of three Maryam Mirzakhani New Frontiers prizes, for her contributions to an advanced mathematical theory.

UC Berkeley also made a showing in this year’s awards, with postdoctoral fellow Ewin Tang awarded a Maryam Mirzakhani New Frontiers Prize for her work in quantum computing.