By NICOLE WINFIELD, Associated Press

VATICAN CITY (AP) — Pope Francis changed the Catholic Church’s teaching in areas such as the death penalty and nuclear weapons, upheld it in others such as abortion, and made inroads with Muslims and believers who long felt marginalized.

Where Francis, who died on Monday, stood on key issues:

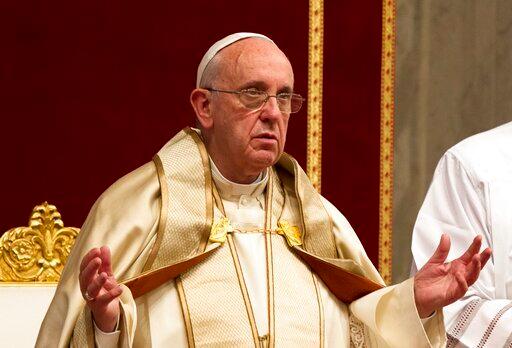

FILE – Pope Francis, flanked by Monsignor Georg Gaenswein, listens to a faithful’s speech on the occasion of an audience in the Paul VI hall at the Vatican, Friday, March 22, 2019. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia, file)

Abortion

Francis upheld church teaching opposing abortion and echoed his predecessors in saying that human life is sacred and must be defended. He described abortion, as well as euthanasia, as evidence of today’s “throwaway culture” and likened abortion to “hiring a hit man to resolve a problem.”

But he didn’t emphasize the church’s position to the extent his predecessors did, and said women who had abortions must be accompanied spiritually by the church. Francis also allowed ordinary priests — not just bishops — to absolve Catholic women who had intentionally terminated a pregnancy.

He didn’t approve of attempts by U.S. bishops to deny Holy Communion to President Joe Biden because of his abortion-rights stance, saying bishops should be pastors, not politicians.

Abuse

Francis’ greatest scandal of his papacy was when he discredited Chilean sexual abuse victims by siding with a bishop whom they accused of complicity in the abuse. After realizing his error, he invited the victims to the Vatican and apologized in person. He then brought the entire Chilean bishops conference to Rome where he pressed them to resign.

In his most significant move, Francis defrocked former U.S. Cardinal Theodore McCarrick after a Vatican investigation determined he abused minors as well as adults. Francis later passed church laws abolishing the use of pontifical secrecy and establishing procedures to investigate bishops who abuse or cover up for predator priests.

But he was dogged by some high-profile cases where he seemed to side with accused priests.

Benedict

In 2013, Pope Benedict XVI resigned in the first such papal retirement in 600 years, and Francis was elected to replace him.

With Benedict living on the Vatican grounds until his 2022 death, Francis said it was like having a “wise grandfather” at home, part of his belief the elderly have a wealth of experience to offer.

There was friction at times, however, including when Benedict co-authored a book strongly backing priestly celibacy at the precise moment Francis was considering an exception to resolve a clergy shortage in the Amazon.

He praised Benedict for humility and courage by setting a precedent for retired popes, although after the German-born pontiff died, Francis said the papacy should be a job for life.

Capitalism

Some conservative U.S. commentators accused Francis of having Marxist sympathies, given his frequent denunciations of economic systems that “idolize” money over people and clear distaste for U.S.-style capitalism.

He called for a universal basic income, dignified wages and working conditions, and said that while globalization had saved many from poverty, “it has condemned many others to die of hunger because it’s a selective economic system.”

“This economy kills,” he said of globalization, defending his positions as those of the Gospel, not communism.

Celibacy

Francis upheld celibacy for Latin Rite priests even after bishops from the Amazon asked him to make an exception to allow married priests to address a shortage of clerics.

Francis had long said the celibacy requirement could change, since it was not a matter of doctrine. But he said the debate was too politicized and that he didn’t want to be the pope to take the step.

China

In 2018, Francis authorized a deal over bishop nominations in China to end a decades-long dispute and regularized the status of a half-dozen Chinese bishops who had been consecrated without papal consent.

FILE – Pope Francis poses a group of faithful and bishops from Shanghai during his weekly general audience in St. Peter’s square at the Vatican Wednesday, May 22, 2019. (AP Photo/Alessandra Tarantino, File)

Details of the accord were never released, but his conservative critics bashed it as a sellout to communist China, while the Vatican defended it as the best deal it could get before Beijing closed the door entirely.

Contraception

Francis defended the church’s opposition to artificial contraception, but he also said Catholics need not breed “like rabbits” and should instead practice “responsible parenthood” through approved methods.

The church endorsed the Natural Family Planning method, which involves monitoring a woman’s cycle to avoid intercourse when she is ovulating.

At the same time, Francis suggested in 2016 that women threatened with the Zika virus — which was causing malformations in thousands of children at the time — could use artificial contraception because “avoiding pregnancy is not an absolute evil” in light of epidemics.

COVID-19

Like the rest of humanity, Francis was grounded during COVID-19, prevented from traveling, celebrating Mass in public or presiding over audiences. He repeatedly urged the world to use the pandemic as a wake-up call showing the need to reset priorities and policies in favor of the most vulnerable.

Francis strongly supported vaccination campaigns and demanded the poor have priority. The Vatican’s doctrine office said it was morally acceptable to be vaccinated, even with shots that used cell lines from aborted fetuses in research and production processes, putting Francis at odds with conservatives who refused the shots on moral grounds.

Death penalty

Francis went beyond his predecessors and changed Catholic teaching to state that the death penalty is “inadmissible” in all cases, regardless of the severity of the crime.

Francis also called life in prison without parole a “hidden death penalty” and solitary confinement a “form of torture,” saying both should be abolished.

Divorce

Francis divided the church by issuing an opening to divorced and civilly married Catholics to receive Communion.

Church teaching holds that, without a church-issued annulment declaring the initial marriage invalid, these Catholics are committing adultery and thus cannot receive the sacrament.

Francis first made it easier to get an annulment. Then, he didn’t create a blanket admission to the sacraments to these Catholics without one, but in a footnote to his 2016 encyclical “The Joy of Love,” he suggested bishops and priests could accompany such couples on a case-by-case basis.

Environment

Francis became the first pope to use scientific data in a major teaching document by calling global warming a largely human-caused problem.

In his 2015 encyclical “Praised Be,” Francis denounced a “structurally perverse” world economic system that exploits the poor and risks turning the Earth into an “immense pile of filth.” A 2023 update singled out the U.S. for its emissions and warned the world was “nearing a breaking point.”

He pressed the issue at a 2019 meeting of bishops from the Amazon and in his preaching on the coronavirus pandemic. While Francis pressed the ecological issue harder than his predecessors, many popes before him called for better care for God’s creation.

Indigenous peoples

Francis made sweeping apologies for the “crimes” against Indigenous peoples during the colonial and post-colonial conquest of the Americas.

He apologized in Bolivia in 2015 and again during a “penitential pilgrimage” to Canada in 2022 for the church’s role in the forced assimilation of Indigenous children in church-run residential schools.

The Vatican also formally repudiated the “Doctrine of Discovery,” theories backed by 15th century “papal bulls,” or charters, that legitimized the colonial-era seizure of lands and form the basis of some property laws today, even though it didn’t rescind the bulls themselves.

Francis also held up as a model economic system the Jesuit-run missions in Paraguay that brought Christianity and European-style education and economic organization to the natives in the 17th and 18th centuries.

He canonized the 18th century missionary Junipero Serra during his 2015 trip to the U.S. over objections from some Native American groups who accused Serra of forced conversions, enslaving converts and helping wipe out Indigenous populations through disease.

Islam

Francis made significant progress in the Vatican’s troubled relations with Islam by forging ties with Sunni and Shiite religious leaders and emphasizing a shared commitment to peace, solidarity and dialogue

FILE – Sheikh Ahmed el-Tayeb, right, Grand Imam of Al-Azhar, the pre-eminent institute of Islamic learning in the Sunni Muslim world, right, welcomes Pope Francis at the international peace conference in Cairo, Egypt, Friday, April 28, 2017. (AP Photo/Amr Nabil, file)

He signed a landmark document on the need for greater human fraternity with Sheikh Ahmed al-Tayeb, the grand imam of Al-Azhar, the seat of Sunni learning in Cairo.

He was the first pope to visit both the Arabian Peninsula and Iraq, the birthplace of Abraham, a prophet important to Christians, Muslims and Jews. While in Iraq, he met with the country’s top Shiite cleric and a revered figure in the Shiite world, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani.

Latin Mass

In one of his most controversial moves, Francis reversed Benedict and reimposed restrictions on celebrating the old Latin Mass. Francis said he had to act because the spread of the so-called Tridentine Rite after Benedict relaxed restrictions in 2007 was becoming a source of division in the church.

This outraged his traditionalist and conservative critics, who called the move an attack on them and the ancient rite. It fueled right-wing opposition to Francis that already was angered at his outreach to gays and divorced Catholics.

LGBTQ+

Francis famously said, “Who am I to judge?” when asked in 2013 about a Vatican monsignor who was purportedly gay.

FILE – Pope Francis walks in procession on the occasion of the Amazon synod, a three-week meeting on preserving the rainforest and ministering to its native people, at the Vatican, Monday, Oct. 7, 2019. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini, file)

Francis followed up by assuring gay people that God loves them as they are, that “being homosexual is not a crime,” and that “everyone, everyone, everyone” is welcome in the church.

During his pontificate, the Vatican reversed itself and said transgender people could be baptized, serve as godparents and witnesses at weddings; and approved same-sex blessings. But while he met several times with members of the LGBTQ+ community, Francis didn’t change church teaching stating that homosexual acts are “intrinsically disordered.”

As archbishop of Buenos Aires, he opposed efforts to legalize same-sex marriage and proposed, unsuccessfully, that the country approve civil unions instead.

He articulated support for those Argentine civil union protections in a 2019 interview with Mexican broadcaster Televisa, making him the first pope to come out in favor of them.

Migration

Francis denounced the “globalization of indifference” shown to migrants and urged Europe and other countries to open their doors to those seeking better lives.

His first trip outside Rome as pontiff in July 2013 was to the Italian island of Lampedusa, a key site in Europe’s migration crisis.

In 2016, he brought a dozen Syrian refugees to Rome with him from a camp in Greece and repeated the gesture in 2021 while visiting Cyprus and Greece. “We cannot allow the Mediterranean to become a vast cemetery!” he told European lawmakers.

He also decried “inhuman” conditions facing migrants crossing the U.S.-Mexico border. In 2016, Francis said of then-candidate Donald Trump that anyone building a wall to keep migrants out “is not a Christian.”

Nuclear weapons

Francis went further than his predecessors — and church teaching — by saying that not only the use, but the mere possession of nuclear weapons was “immoral.”

The church previously held that nuclear deterrence could be morally acceptable in the interim as long as it went toward mutual, verifiable disarmament.

Vatican reform

Francis was elected on a mandate for bureaucratic reform after centuries of waste, mismanagement and market crises put the Vatican’s financial health at risk.

FILE – In this Feb. 19, 2014 file photo, Pope Francis greets U.S. cardinal Theodore Edgar McCarrick at the end of his general audience, in St. Peter’s Square at the Vatican. (AP Photo/Alessandra Tarantino, file)

He imposed regulations to bring order, transparency and modern accounting to the books, requiring competitive bidding procedures, caps on gifts, salary cuts for cardinals and the centralization of assets and investments in one office with a unified, ethical and green investment policy.

He created a Secretariat for the Economy to supervise the Holy See’s finances, staffed mostly with lay experts, and he authorized a sweeping criminal trial into the Vatican’s botched investment in a London real estate deal that resulted in losses of tens of millions of euros.

Women

Francis consistently called for a greater role for women in governing the church and made significant appointments and changes to church law to prove his point.

He named an Italian nun as prefect of the Vatican office for religious orders and another Italian nun as head of the Vatican City State administration, two jobs previously held only by cardinals. He also named a French nun as an undersecretary in the Vatican Synod of Bishops’ office, giving her a vote in the previously all-male process and opened up the synod itself to voting women members.

He named three women to the Vatican office that vets bishop appointments, a first. He appointed women to half the seats on the Vatican’s economic council, appointed two study commissions into whether women could be ordained deacons, put Mary Magdalene on par with the male apostles by declaring a feast day for her, and formally allowed women to serve as lectors and acolytes, services previously open to them on an ad hoc basis.

But he reaffirmed the all-male priesthood and ruled out, for now, ordaining women as deacons.