The plan had always been to seek asylum in the U.S.

But somewhere on the journey between their home in El Salvador and the northern Mexico border, Wilver Arteaga and his family realized there was no way.

The strong rhetoric around President Donald Trump’s immigration policies was becoming reality, and on his first day in office, he shut down the legal appointment process for migrants to be screened for asylum.

Arteaga, 40, and his wife used to be security guards. They were rule-followers. It was time to come up with a backup plan.

They are now among the nearly 20,000 refugees or asylum seekers living in Baja California — most of them in Tijuana.

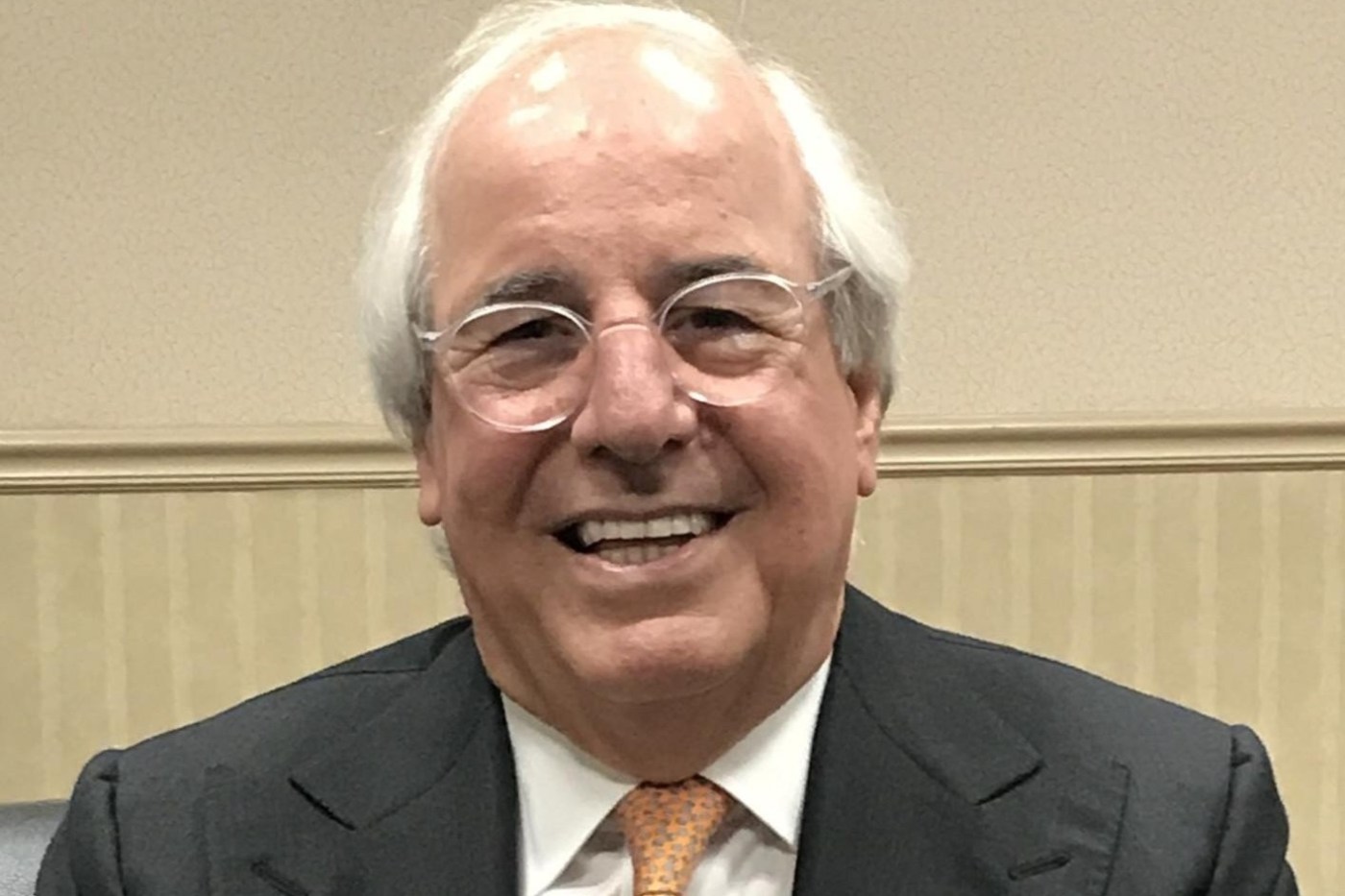

Wilver Arteaga comforts his 3-year-old son while walking back to a shelter on April 11 in Tijuana. (Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

“When that legal option was no longer available, I resigned myself,” he said.

Tijuana has always been a place of waiting for migrants. It’s one of the main entry points to the U.S. for thousands arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border, many of whom are seeking asylum. However, faced with increasingly severe roadblocks to crossing into the U.S., whether legally or illegally, the sprawling border city has lately become a place to call home.

From January to May, 901 people filed for asylum in Baja California, according to data shared by the Baja California office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

The largest monthly jump in applications took place from January to February, nearly tripling from 124 to 331, following the Trump administration’s shutdown of the CBP One asylum appointment process. Under the Biden administration, this step was required for asylum seekers to legally present themselves for screening at a U.S. port of entry.

“Tijuana is an appealing place for asylum seekers and refugees,” said Dagmara Mejía, head of the UNHCR office in Baja California and Sonora. “There are jobs available, and the pay is good. People also say that they don’t feel discriminated against here, and there’s a solid network of people who have settled here and spread the word.”

There are also challenges, including a monthslong waiting period to process asylum claims, expensive housing, difficulties earning a living as an undocumented worker and high crime.

Many said they have accepted their new reality.

Recent news from the U.S. of stepped-up immigration raids and calls from the Trump administration to “self-deport” only validates the decision to try to make a go of it in Mexico.

Wilver Arteaga walks with his son to speak with a lawyer in Tijuana. (Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Most of the nearly 80,000 asylum seekers arriving in Mexico last year came from Honduras, Cuba, Haiti, El Salvador and Venezuela, according to an April UNHCR report. More than half reported leaving their home countries due to violence, insecurity or threats.

Returning home is not an option for many.

Navigating challenges

The Arteaga family had made it to the state of Coahuila when they decided to stay in Mexico. They heard wages were higher in Tijuana, so the couple and their 3-year-old son decided to try their luck there.

Within two weeks of arriving at the Casa del Migrante shelter in Tijuana, Arteaga realized that finding an affordable place to live would not be easy.

“Rents are through the roof,” he said.

Mejía, from the UNHCR, said that asylum seekers usually settle in the Zona Centro area or in eastern Tijuana, urban areas where rents are more affordable.

Arteaga was baffled to discover that many landlords in Tijuana charge rent in U.S. dollars instead of pesos. The apartments he asked about near the shelter ranged from $500 to $800 per month or more in rent.

He thought he found a possibility in a southeastern Tijuana neighborhood, a two-bedroom house renting in pesos. But on the way to check it out with his son, their Uber driver strongly recommended they look elsewhere. The neighborhood was not safe, he told them.

That’s when Arteaga realized he had lots more to learn about the city.

Clothes hang to dry at Iglesia Embajadores de Jesus shelter on April 15, 2025 in Tijuana. (Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Juan Antonio del Monte, a professor and researcher of cultural studies at the Colegio de la Frontera Norte in Tijuana, said that public safety is one of the biggest issues not only for immigrants, but for all residents. “Becoming part of Tijuana involves facing the city’s challenges,” he said.

The latest National Urban Public Safety Survey, which is conducted in Mexico on a quarterly basis, indicates that 63% of adult residents in Tijuana feel unsafe.

Lingering anti-immigrant discrimination, which boiled over in 2018 with the arrival of Central American caravans in Tijuana, has also been a concern.

Del Monte said that migrants often tell him during their conversations that they have found their “angels” — people who lend them support — but that some also face some form of discrimination or xenophobia.

“Tijuana and its residents are hospitable, and that should be recognized,” he said. “But we must also acknowledge that some people openly express anti-immigrant sentiments.”

Soraya Vázquez, deputy director for Al Otro Lado, a binational organization that provides legal aid to migrants, noted how the situation has changed over the years. “There will always be people against immigration,” she said. “But that doesn’t mean it’s a widespread or prevailing attitude in the city.”

Finding acceptance

José Hernández, who fled persecution in Guatemala as a gay man, has found Tijuana to be a refuge — a “land of many colors,” he says.

“There is a lot of diversity. There are many nationalities,” he said. “I feel accepted here.”

Even before Trump returned to office, Hernández, 27, had struggled daily to secure an appointment through the CBP One app. The stress was too much to bear. In October, he decided to stop trying. He didn’t even speak English, he reasoned.

His partner eventually got an appointment and crossed into the United States. Hernández stayed behind.

“I’m starting from scratch,” he said. “I don’t regret my decision. It was at that moment that I was finally able to start planning my life.”

José Hernández sells clothes outside of a shelter he’s staying at on May 8 in Tijuana. (Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

With his savings, he bought a table and clothes to sell at a street stand outside the shelter, where Hernández lives. “Maybe it’s not much,” he said of his small business. “But it has come with a lot of effort and sacrifice. I am very happy with what I have achieved because it is my small legacy, which I hope to grow more with discipline and effort.”

Such alternative ways to earn a living are common among asylum seekers, who aren’t legally allowed to work in Mexico while their applications are pending.

Mexico no longer issues the so-called humanitarian visitor cards that allowed asylum seekers to work while their cases were being reviewed. Advocacy workers say that this is one of the most frequently mentioned concerns among asylum seekers.

Still, many find a way. According to UNHCR data, 80% of the nearly 20,000 asylum seekers and refugees in Baja California last year had a job, either formal or informal.

The asylum process in Mexico is supposed to take about three months, said Mejía from UNHCR, but the number of cases exceeds the capacity of the Mexican Commission for Refugee Aid to process them. Currently, and depending on each case, the process can take between six months and a year, she estimated.

José Hernández sells clothes outside of a shelter. Migrants can’t obtain documentation to work while their asylum applications are being processed, which can take several months. Many turn to informal work to earn a living. (Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Vázquez, from Al Otro Lado, said that the lack of enough interpreters at the commission, known as Comar, is also contributing to the delayed process.

Still, Vázquez believes it’s more likely to obtain asylum in Mexico than in the United States. In the United States, an immigration judge grants asylum claims, whereas in Mexico, Comar, a government agency, makes the decision.

The ‘American dream’ reborn

On a recent Wednesday morning, Vivianne Petit Frère restocked the kitchen of the Haitian restaurant she opened nearly three years ago in Tijuana, readying for the busy lunch rush of fellow expats. Later, on her way to a nearby mall to have her cellphone fixed, friends from Haiti greeted her on the street.

She was a local now.

Besides owning Lakou Lakay, which serves Caribbean dishes such as mixed rice with pork and banana and pork ragout, she attends college and works as a human rights advocate for her community. She can relate to the struggle to get there.

“I came in search of the American dream,” reflected Petit Frère.

Petit Frère’s mother sold their house in Haiti so she could leave the country in search of better opportunities to provide for her mother and two children, who remained behind. Fluent in French, Petit Frère first found a job at a five-star hotel in Brazil. However, when the pandemic hit, things quickly went downhill. So, she began the dangerous journey to the U.S.-Mexico border.

Vivianne Petit Frere brings groceries to her restaurant on June 18 in Tijuana. (Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

By the time she arrived in Tijuana in late 2021, with sights ultimately set on New Jersey, she felt that seeking asylum in the U.S. was one gamble she couldn’t afford. Many Haitians were being expelled under a public health policy at the time.

“I couldn’t afford to be deported, so I didn’t cross,” she said. “I stayed in Tijuana.”

She plugged in to an already vibrant community of Haitian refugees in the border city, many whom arrived following a devastating earthquake that ravaged the island nation in 2010. Nearly half of the asylum seekers and refugees in Baja California since 2019 have been from Haiti, according to the UNHCR.

Related Articles

Tesla goes to trial over fatal autopilot crash

The tariff-driven US inflation that economists feared begins to emerge

A California judge’s ruling on immigration raids ripples across nation. Here’s what you need to know

Two Democrats and a Republican went to a California ICE detention center. Only one got in

As Children’s Hospital LA closes its gender-affirming care center, advocates worry kids’ lives are ‘on the line’

She spent her first nights in a Tijuana park alongside other Haitians until she found a place to stay. She knocked on doors looking for work and eventually landed her first job as a cleaner.

With practice and the help of translation apps on her phone, she learned to speak Spanish.

Petit Frère shares an entrepreneurial spirit common among migrants. “There are no jobs in Haiti,” she said. “So, if you want to make money, you have to find a way to start your own business.”

She opened her restaurant in Tijuana’s Zona Centro in 2022. Though she envisioned it as a way to serve her community, it has also become a means of sharing her culture with the city.

Vivianne Petit Frere greets a friend’s child. (Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

She is currently studying social work in college and pursuing a diploma in restaurant management. She is also the Tijuana representative of the nonprofit Haitian Bridge Alliance.

Petit Frère had a daughter in Mexico. Later, the rest of her family immigrated to Tijuana from Haiti. They are now all legal residents.

In hindsight, she said she realized she had found what she was looking for in Tijuana. Or maybe she has even bigger dreams.

A home of their own

Other migrant families have found the same sense of stability in the city of nearly 2 million inhabitants.

For the Miranda family, who fled El Salvador to escape violence in their town, fate intervened in their plans.

Rocío Ramos, right, helps her daughter, Abigail, 7, with schoolwork in their home next to the Iglesia Embajadores de Jesus shelter on May 19 in Tijuana. (Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

In early 2023, on the day they were scheduled to show up at the port of entry to request asylum, an intense storm turned dirt roads to muddy rivers. The van from the shelter that had been prepared to take them to the border couldn’t leave.

“What if we stay in Mexico?” Josué Miranda wondered aloud to his wife.

“She said to me, ‘How is that possible? The journey was too tough to stay here,’” he recalled.

There were several questions that had to be considered. How to make a living? Where to live?

As time passed, they found answers: his wife, Rocío Ramos, opened a food stand outside the Embajadores de Jesús shelter, and Josué became a close collaborator of the shelter’s director.

Josué Ramos helps build homes for several families at the Iglesia Embajadores de Jesus shelter. (Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Last year, they were given the opportunity to build their own house on the shelter’s grounds. It’s part of the shelter’s program to provide housing for people who decide to settle in Tijuana.

“I never thought I would have a house here one day,” Miranda said.

“Since the day we decided to stay, at no time was there any regret.”

Uncertain future

Many migrants who decided to stay are still charting their paths.

The Artega family, who struggled to find safe, affordable housing, decided to move to Rosarito, about half an hour south of Tijuana. Arteaga’s wife found a job at a local supermarket. Rents are also more affordable there, Arteaga said.

Other asylum seekers are still coming to grips with their new reality.

Ivis Salgado, of Honduras, left, and Milagro Gonzalez leave a shelter that they’re staying at to go to a bus stop to get to work on May 5 in Tijuana. (Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Milagro González, an asylum seeker from Venezuela, had been among the lucky few who had secured an upcoming CBP One appointment — until it was canceled on Trump’s first day in office.

She found a place to stay at a Tijuana migrant shelter, hoping that another option to apply for asylum in the United States would arise. But over time, her hope of crossing the border faded.

González is too afraid to return home, so she began the process of applying for refugee status in Mexico.

“Maybe God didn’t want me on the other side of the border,” she said. “God wants me to learn a lesson here.”