The United Kingdom is now fully enforcing its Online Safety Act, which was passed by Parliament in 2023. The law calls for shielding all users from illegal content with special protections for children, including the use of age assurance tools. Some U.S. states have enacted laws with similar goals, and the U.S. Senate has passed the less ambitious Kids Online Safety Act (KOSA), which has not yet passed the House.

Related Articles

Magid: How to organize, search and print your digital photos

Magid: Paying forever? Subscriptions are taking over tech

Magid: Internet Governance Forum focuses on protecting kids

Magid: The disappearing off switch

Magid: Designing digital safety with youth in mind

UK law

For all UK users, including adults, the Online Safety Act requires services, including search engines and social media platforms, to take proactive steps to block content that promotes terrorism, child sexual abuse material, hate crimes and revenge porn along with fraud and scams.

And there are additional provisions for children regarding harmful content. Services likely to be accessed by children must proactively assess the risks features, algorithms, and content for different age groups, with specific measure to address risks such as material that encourages suicide, self-harm, eating disorders, bullying, hateful abuse, dangerous stunts or exposure to pornography.

Age verification

This week, the UK began enforcing the requirement that platforms use highly effective age assurance technologies, not just requiring users to state their age, to prevent children from accessing adult content.

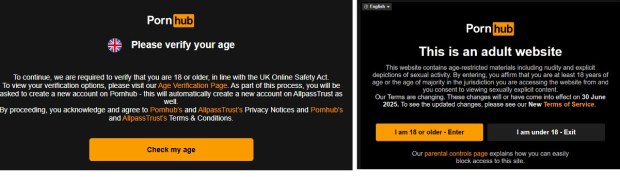

Already, adult sites such as Pornhub are requiring users to sign in to access their content, which is legal for adults but off-limits for those under 18. I tested this by using a virtual private network to make it appear as though I was logged on from the UK and got a page requiring age verification. Users can verify their age using biometric age estimation (such as a selfie analyzed by AI), uploading a government-issued ID, or verifying age through a credit card or other financial data.

Without the VPN, users logging in from most U.S. states and other countries are only required to state that they are 18 or older. A growing number of U.S. states now also require adult sites to verify the age of their users, so whether users see an age verification page depends on what state they log in from.

UK site (left) requires age verification but not US site

Some argue that this requirement puts a chilling effect on free speech because it removes the anonymity of visitors. There is a counter argument that it’s no different from adult theaters that have long banned underage patrons, but there is a difference between having to flash your ID at the door (assuming they ask for ID) and putting your name or other personal information into an online database.

The law is regulated by Ofcom, the UK’s independent regulator for communications. It has published guidelines for industry that also require them to protect the privacy of adult patrons. But that does not completely eliminate the possibility of a data breach or other privacy threats to adults who might worry about disclosure of their interest in this content.

Child friendly design

The UK’s Online Safety Act goes beyond just restricting harmful content. It requires platforms to be designed with children in mind, offering clear reporting tools, easy-to-understand terms of service and real support when problems come up. Services that fail to comply can be hit with heavy fines or have access blocked in the UK.

The UK is far from alone in pushing legislation to protect children online. Last year, Australia passed a law banning anyone under 16 from accessing social media. I spoke out against that and similar proposals during a session at this year’s UN Internet Governance Forum, arguing that although these measures may be well-intentioned, they risk violating young people’s free speech rights and access to potentially life-saving information. For many marginalized youth, social media is a vital source of support, connection and community.

U.S. law

The United States doesn’t have a comprehensive national online child protection law, though several states have passed laws, and Congress for years has been debating the Kids Online Safety Act (KOSA), co-sponsored by senators Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) and Marsha Blackburn (R-TN). The bill, which is designed to hold platforms legally accountable for protecting young users, passed the U.S. Senate in July 2024 by a wide margin (91–3). It has not yet been taken up in the House of Representatives.

KOSA would require platforms “to provide minors with options to protect their information, disable “addictive” features, and opt out of personalized algorithmic recommendations,” according to Blumenthal. It would also require “the strongest privacy settings for kids by default,” and give parents “new controls to help protect their children and spot harmful behaviors and provide parents and educators with a dedicated channel to report harmful behavior,” according to Blumenthal’s office.

Platforms would also be required to “prevent and mitigate specific dangers to minors, including promotion of suicide, eating disorders, substance abuse, sexual exploitation, and advertisements for certain illegal products (e.g. tobacco and alcohol).”

Despite its overwhelming support in the Senate, it’s unclear whether it will pass the House. Several members, including speaker Mike Johnson (R‑LA), have expressed concern over its impact on free speech. “I think all of us, 100 percent of us, support the principle behind it, but you’ve got to get this one right,” he said. “When you’re dealing with the regulation of free speech you can’t go too far and have it be overbroad, but you want to achieve those objectives. So, it’s essential that we get this issue right.”

Just as there is bipartisan support for KOSA, there is also ideologically diverse opposition. The ACLU said that the “bill would not keep kids safe, but instead threaten young people’s privacy, limit minors’ access to vital resources, and silence important online conversations for all ages.” The ACLU also said that it could restrict adults’ freedom of expression online and limit access to a broad range of viewpoints.

GLAAD, formerly the Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation, was initially opposed to the bill and then withdrew its opposition after some amendment, but it’s once again opposed. GLAAD spokesperson Rich Ferraro, told the Washington Post, “When reviewing KOSA, lawmakers must now take recent, harmful and unprecedented actions from the FTC and other federal agencies against LGBTQ people and other historically marginalized groups into consideration.”

As lawmakers in the U.S. debate how far to go in regulating online platforms, some are looking to the UK for inspiration, much as California did with its 2022 Age‑Appropriate Design Code Act, modeled after the UK’s 2020 version. But where the U.S. goes from here remains uncertain in a country where concerns about free speech, privacy and government overreach are deeply rooted. One thing is clear: the status quo is no longer acceptable to many parents, advocates, and even tech companies who say it’s time to strengthen protections for kids online without undermining the rights, voices and access to information that everyone, including youth and marginalized communities, depends on.

Related Articles

Gov. Newsom seeks $18 Billion for utilities’ wildfire fund as California faces future blazes

Bay Area 2050 plan moves to next phase

Former Birkenstock site in Marin County sold to Eames Institute for $36 million

Value of homes impacted by California wildfire totaled almost $52 billion

Berkeley’s new accessory dwelling unit policy aims for balance

Larry Magid is a tech journalist and internet safety activist. Contact him at [email protected].