SAN JOSE — It took two near-death experiences before 36-year-old Joshua Anthony Hernandez was ready to put his life as a gangster in the rearview mirror.

He recovered from a near-fatal drug overdose just in time to get indicted in one of the biggest racketeering cases in California history. Months later, while incarcerated at Dublin’s Santa Rita Jail, he was cornered in a cell by three others, his face sliced open in what he now says was a moment that led to empathy and greater understanding of the similar harm he’d inflicted on others.

Related Articles

San Jose cat adoption center closes following car crash

San Jose: Silver alert issued for missing 78-year-old man

Newsom commutes sentence of man convicted in Bay Area murder-for-hire plot

A closer look: What’s behind San Jose’s extraordinarily high homicide clearance rate?

Mother-daughter pair held to answer felony charges in San Jose daycare drownings

After that, the onetime Norteño gang leader found a new calling: jailhouse muralist, through a volunteer program aimed at giving Alameda County inmates a positive outlet, court records show. That change in direction may have yielded Hernandez a shorter sentence when he faced a judge last month.

In the early 2020s, Hernandez gained a reputation among federal law enforcement as “Sleepy G,” a so-called “shot caller” in the San Jose Grande gang with the power to order violence at a whim. Now in 2024, here he was gaining notoriety among law enforcement for the opposite reason: his passion for art and hard work, painting murals with life lessons and encouragement.

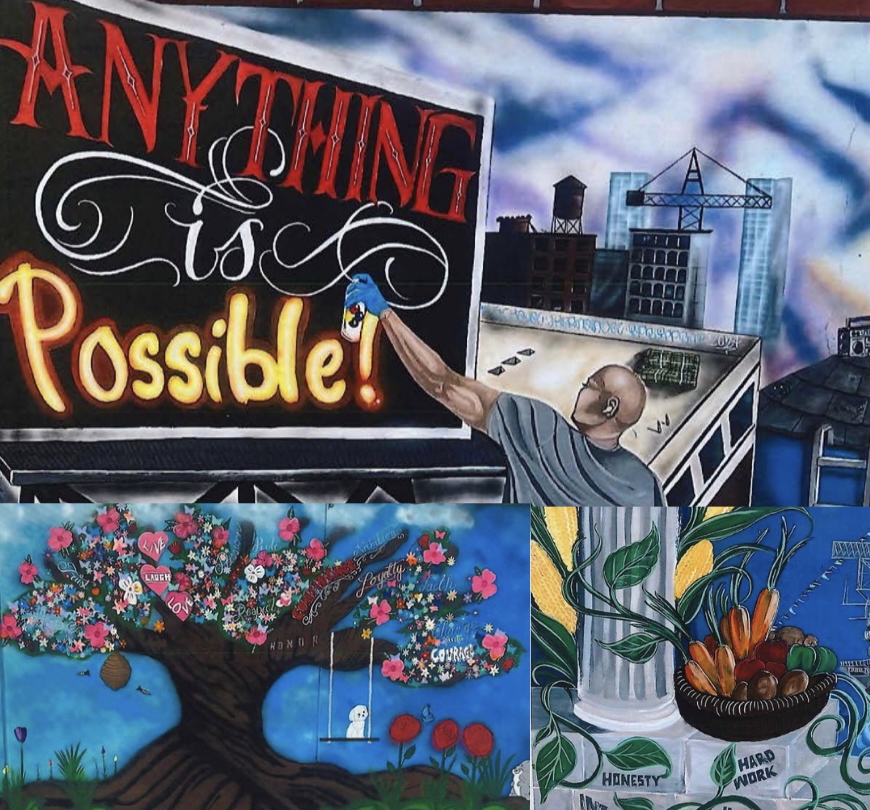

One depicts a a colorful tree with hearts that read, “live, laugh, love.” Another depicts a panoramic of the East Bay, with “we are the pillars of our community” written in cursive. Another shows a man spray-painting a billboard in red and yellow letters reading: “Anything is possible.”

“His talent both in mural painting and as a tattoo artist is legendary,” Hernandez’s lawyer, Michael Stepanian, wrote in court filings. “He is leaving Santa Rita in a better condition than when he arrived.”

The long, bumpy road to gangster to craftsman started in September 2021, when Hernandez took too many Percocet pills and passed out. His heart stopped for 45 minutes, and he went into a three-day coma, he wrote in a letter describing the experience. When he came to, it was just in time for prosecutors in San Jose to hit him with one of the biggest federal indictments the region has ever seen.

“I was hooked up to a respirator because I could not breath on my own,” Hernandez wrote. “The doctor told my mom I would be brain dead if I ever woke up. He said I would never be the same if I ever woke up.

“When I did wake up, my life was changed forever.”

All told, federal prosecutors charged 54 people in 16 cases with various federal offenses. The defendants were in one way or another all connected to the Nuestra Familia prison gang, which oversees Norteño subsets across Northern California and beyond. There was an incredible range of experience and criminality — some defendants were convicted murderers, charged with arranging more mayhem from their cells. Others were simply associates of gangsters, or even their wives or girlfriends, charged with playing a small role in a drug deal or arranging to destroy evidence.

Hernandez’s charges were serious. He was accused of arranging the 2019 robbery of a “dope house” — one of several robberies he allegedly committed for the gang — and of stabbing a man who’d disrespected a murdered Norteño member by rifling through the man’s pockets when he was shot and killed in 2013. Prosecutors also noted his eight prior felony convictions since 2007, including for domestic violence and gun possession, court records show.

But after his indictment, a judge showed Hernandez some good will, paving the way for his release on $25,000 bond. Hernandez responded by absconding from pretrial release, remaining a fugitive for nearly three years, until his eventual arrest in January 2024. He was sent to federal detention at Santa Rita Jail, but by then he’d lost interest in being a gangster, he wrote.

“I was blinded by the fake dream that gang members sell to each other. So I was willing to do anything that I could to boost my reputation in the gang,” Hernandez wrote. “I thought that by doing these things I would get the love that I wanted. Love that I thought was real. Gangs feed off of that.”

He began to vocalize thoughts like this around the jail, drawing the ire of other incarcerated gang members; three of them would go on to trap him inside a cell and slice open his face. For Hernandez, this brought back memories of when he committed a similar crime against someone who he believed had turned their back on his gang.

“I now understand what my victim felt. What his family felt. I am filled with remorse, regret, sympathy, and I just wish I could erase that pain,” Hernandez wrote.

He decided to plead guilty, admitting to the stabbing, the $27,000 stash house robbery, and to membership in the SJG gang. He signed up for classes, and began volunteering in the mural program, applying his skills as a tattoo artist to the walls of jail yards.

“Hernandez has an excellent work ethic and is very respectful of staff and co-workers. He frequently takes the lead and directs other inmates on painting the murals at SRJ,” Alameda County Deputy Brandon Sill wrote in a memorandum later filed in court.

In early August, it was time for U.S. District Judge Yvonne Gonzalez Rogers to sentence Hernandez. Prosecutors asked for an seven-year prison term but argued that Gonzalez Rogers should give him 70 months at an absolute minimum, writing in a memo that he helped perpetuate the type of violence that “holds our communities hostage.”

“He inflicted significant violence on another SJG member for a perceived violation of the gang’s rules, stabbing him multiple times to send a message to other gang members,” the prosecution sentencing memo says. “He also engaged in multiple robberies involving the theft of drugs and money, one of which resulted in the residents of the stash house shooting at Hernandez and his coconspirators from the porch, hitting Hernandez’s co-conspirator.”

In the end, Gonzalez Rogers gave Hernandez a five-year prison term. Factoring in the time he’s already spent in jail, the decision paves the way for his release in 2028. In his letter filed in court, he says he has a game plan for what to do as a free man.

“I am going to go home and teach people to believe in themselves. I want people to know that they don’t have to join a gang to find love. You don’t have to put your energy into a gang,” Hernandez wrote, later adding, “When you believe in yourself anything is possible.”