By Khari Johnson and Yue Stella Yu, CalMatters

In April, Rhode Island resident Navah Hopkins received a plea for her help to defeat legislation thousands of miles away in California.

The ask came from Google, maker of the world’s most used web browser, Chrome. The tech giant sent a message to an email list that Hopkins and other small business owners were subscribed to. Google’s request: To sign a petition opposing Assembly Bill 566, which would require browsers to provide users with a way to automatically tell websites not to share their personal information with third parties. The measure is sponsored by the California Privacy Protection Agency, which enforces state regulations on such sharing.

Related Articles

Meta, OpenAI face FTC inquiry on chatbot impact on kids

Google sued over monopoly violations by advertising exchange

Google hit with $3.5 billion fine from European Union in ad-tech antitrust case

Appelbaum: Why Google’s antitrust loss is a victory for the Valley

Waymo robotaxis coming to Mineta San Jose International Airport

In its email to Hopkins, Google claimed that the legislation would “hurt your ability to use online ads to reach customers.”

“It was intentionally misleading people that by this bill passing, they were going to lose out on all of these tools within Google (to advertise),” she told CalMatters.

The outreach was particularly noteworthy because Google had not itself taken a public position on the bill. The tech giant was so quiet about its opposition that Assemblymember Josh Lowenthal, the author of AB 566, did not know about Google’s email push until a CalMatters reporter asked. Lowenthal also said his office did not receive small business owners’ signatures or outreach.

Google’s name wasn’t on the petition either; instead, the document was officially from the “Connected Commerce Council,” which the tech giant backs financially.

The largely behind-the-scenes campaign offers a glimpse into how the tech giant is working to preserve its grip on the online advertising market and how it attempts, without being seen, to shape policies in a state with one of the nation’s strictest privacy protection laws.

Recruiting small businesses to represent the policy interests of a tech giant isn’t new. Last year, Google successfully blocked a similar bill — ultimately vetoed by Gov. Gavin Newsom — by adopting the same tactic, reaching out to small businesses via email lists, according to a message obtained by CalMatters.

There’s no telling how effective Google’s lobbying on the measure has been this year, or how many people it successfully mobilized. Experts warn that the strategy could backfire if the people it reaches out to, like the small business owners, aren’t buying what the company is selling.

But before the browser bill reached its final floor vote, Lowenthal amended it to delay the effective date until 2027 and to add liability protections for browser companies like Google.

When asked who advocated for that language, Lowenthal said he’d taken input from “colleagues and stakeholders” to shape up the “strongest possible bill.”

“With any bill that’s been vetoed before, it takes some give-and-take to get it across the finish line,” he said.

Google did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Google ranked among the most active lobbyists in California last year, spending more to influence the opinions of elected officials than it had in the previous 20 years combined. The lobbying was aimed at battling AI regulation, local news funding requirements, and a prior version of the browser bill.

This year, it has disclosed pouring nearly $700,000 into lobbying state leaders on bills including AB 566. Google has also increased lobbying spending in many other statehouses, according to the Open Markets Institute. With inaction in Congress, states have led the way in tech regulation in recent years.

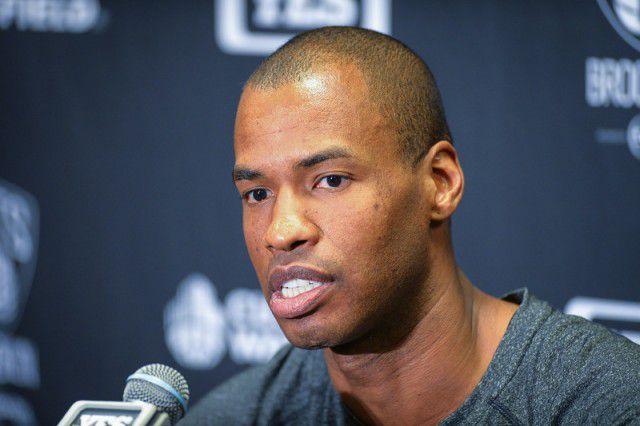

Assemblymember Josh Lowenthal at the dais during an Assembly floor session at the state Capitol in Sacramento on Aug. 21, 2025. Photo by Fred Greaves for CalMatters

But it’s hard to trace Google’s full influence when the company does not publicly share its position on bills like AB 566, instead paying groups like the California Chamber of Commerce and Connected Commerce Council to influence legislators on its behalf.

Google registered to lobby 17 bills this year that sought to do things like place warning labels on social media or protect people from algorithms that make health care decisions, but the company only publicly stated its position on one bill that sought to require online age verification, according to state filings and Digital Democracy.

Google’s lobbying tactics, while not illegal, demonstrate the sway money has over policies, said Sean McMorris, the transparency, ethics, and accountability program manager at California Common Cause.

“This type of activity … exemplifies the skewed playing field that we have to play on,” he said. “It’s important to report on and to point out these strategies and loopholes that money can afford you the privilege to engage in, and the public has every right to scrutinize whether that is just or not.”

If Google really believes this bill shouldn’t become a law, its lobbyists should show up to testify at a public hearing, not behave in shadowy ways that undercut democracy, said Brandon Forester, an organizer for MediaJustice, a nonprofit that has been critical of the influence of of Big Tech companies and internet service providers.

“None of us wants to enter a surveillance marketplace every time that we go on the internet,” he said. “Part of the reason they need to do the shadow lobbying is because the things that they want to do to achieve their infinite growth model is not good for the public.”

AB 566 is not the only threat Google faces to its grip on how people surf the web. A judge ruled last month that the company may no longer enter into exclusive distribution deals for Chrome or Google search. And Chrome faces new competition from a number of AI-powered browsers entering the market, reportedly to soon include one from ChatGPT maker OpenAI.

Onerous mandate or consumer convenience?

Under a 2018 state law, California businesses must provide customers with a way to forbid the sharing or sale of their personal information to businesses. AB 566 seeks to streamline that process.

Browsers such as DuckDuckGo, Brave, and Firefox already have privacy features that, once enabled, automatically send an opt-out signal to each website the user goes to.

The California Chamber of Commerce opposes AB 566, arguing it represents an onerous mandate. The measure lacks clarity, regulates browsers that aren’t “consumer-facing” and is hard to implement, the trade association argued in a letter to lawmakers.

“Browsers and devices already compete to offer clear, effective privacy controls,” Ronak Dalami, a lobbyist for the chamber, told lawmakers in July.

A similar bill the Legislature passed last year would have required both web browsers and mobile operating systems to offer ways to automatically prohibit the sharing of a user’s personal information, but Gov. Gavin Newsom vetoed the bill because no major mobile operating system includes such an option.

“To ensure the ongoing usability of mobile devices, it’s best if design questions are first addressed by developers, rather than by regulators,” Newsom said in a veto message.

Bianca Blomquist, California director of nonprofit Small Business Majority, which represents 85,000 small businesses nationwide, was among the business owners who received an email last year from Google, on a mailing list of businesses that participated in the company’s training program, Grow with Google. The letter argued that allowing people to easily stop companies from sharing their personal information would make it more expensive for small businesses to sell their products.

But Blomquist was skeptical. And while Newsom’s veto message spoke of design risks, she said that most people she talks to “are more concerned about their data being shared than they are too many buttons flashing on a screen.”

To Blomquist, the email is clear evidence that Google was “leveraging” the data it collected from partners for advocacy.

“What we find is that small business owners … and partner organizations oftentimes sign on to support or oppose legislation without having an understanding of what it does.”

Connected Commerce Council

The petition Google circulated this year was authored by Connected Commerce Council, or 3C, a lobbying group that in 2022 claimed to represent 15,000 small businesses but lists Google and Amazon as funders and partners. In 2022, Google and Amazon mobilized their users to fight anti-trust bills in Congress by encouraging them to sign a model online petition the council drafted. That year, the nonprofit published and later removed a membership directory of 5,000 small businesses, many of which told Politico they were not members of the organization.

This spring, the group sent a letter to California state lawmakers, arguing that the requirements proposed in AB 566 would cause small businesses to lose out on customer data and make their websites more expensive to operate.

“Implementing a sweeping experiment that would jeopardize small businesses’ success, limit Californians’ access to relevant products and services, and potentially disrupt access to free web content, is not a sensible way forward,” wrote Rob Retzlaff, executive director of the group.

In a virtual press conference last month, the organization put forward two California online business owners who oppose the legislation. The owners argued that the browser feature mandated in the bill could inadvertently drive away customers, would block them from sending targeted ads to users who opt out of having their personal information shared, and would make it impossible for customers who opted out to opt back in.

“If they opt out of one thing — maybe they just didn’t want … my weekly emails about moms connecting, but they want to have discounts — how are we going to segment that?” said Michelle Mak, owner of baby product store Mewl Baby.

Google did not report paying the commerce council any money to lobby on its behalf to the California secretary of state. But Google reported paying the California Chamber of Commerce, the face of its opposition, almost $100,000 to lobby this year. It also reported paying TechNet, which also registered its opposition, $2,500.

Connected Commerce Council spokesperson Jennifer Hodgkins declined to answer a list of questions from CalMatters, instead providing a statement pointing to the organization’s letters to the Legislature, press releases and statements from small business owners featured in its press conference.

“Small business owners are deeply concerned about the impact AB 566 will have on their ability to advertise online, find new customers, and grow,” Hodgkins said.

John Myers, a spokesperson for the California Chamber of Commerce, declined to answer a CalMatters question about the payments it received from Google.

But McMorris of Common Cause said Google’s payments to the chamber for lobbying should be “closely scrutinized.”

“If it’s not for (AB566), then what was it for?” he said. “That’s where the law gets murky, and you have these wink and nod relationships where both sides know how to play the game without explicitly saying, ‘This is how we are going to play the game.’”

Mobilizing users a unique tactic

It tracks that Google turned to small business owners to protect the company’s business model, said Jeremy Mack, director of the Phoenix Project, a group that tries to draw attention to San Francisco Bay Area front organizations secretly funded by tech billionaires.

Mack said the practice is reminiscent of how Uber and Lyft mobilized people who use ride-hailing apps to support Proposition 22 and keep gig workers from being defined as employees instead of contractors, and tactics embraced by apartment landlords and realtor groups.

“It’s not surprising that Google would do this, but it’s definitely good to be able to flag this for people and put it on their radar,” he said.

Unlike other industries seeking to influence policy, tech companies can mobilize users through their online platforms, said Austin Ahlman, a researcher who tracks Google lobbying efforts in state capitals for the Open Markets Institute. It’s part of a long pattern of tech companies using small businesses that rely on their platforms to preempt regulation.

Meta also has a history of recruiting small businesses to represent its interests, and Google and Meta threatened or prevented people in Australia, Canada, and California from seeing the news to oppose a demand that the companies pay to link to news websites. An earlier, prominent instance of tech companies using their platforms to influence legislation came around the Stop Online Piracy Act and the PROTECT IP Act when major companies, including Google, organized to shut down their websites for a day in September 2012 to oppose those laws.

Mack thinks mobilizing users has been devastatingly effective, but companies probably do it sparingly because if they do it too often people will be more aware of how much control large tech companies have over people’s information.

“I’d call it anti-democratic, but I wouldn’t call it desperate, because, frankly, it mostly works,” he said.

Powerful companies typically combine traditional lobbying and strategies used by civil society organizations when regulatory pressures threaten their core business model, according to a 2023 research paper about corporate lobbying campaigns. Those tactics were historically associated with the fossil fuel, pharmaceutical and tobacco industries, but tech companies have innovated on and rejuvenated the lobbying form. They can do so more effectively because they can tap into user data and their platforms give them unmediated communication with customers.

Companies typically recruit users to advance their policy initiatives when they sense a threat to their business and no longer believe conventional lobbying will be sufficient, said UCLA sociology professor Edward Walker, who studies how companies mobilize customers to speak out about legislation.

But it only works if users are motivated to speak out, such as when video game players fought efforts to regulate in-game violence, or when for-profit college students opposed a push by the Obama administration to keep them from receiving federal student aid.

“It’s important to know that these kinds of grassroots lobbying strategies, or user mobilization strategies, are a double-edged sword. It’s not a given that they’re always going to work in your favor,” he said. “If you do this in a scattershot way, you really increase the risk it’s going to backfire on you.”

The California Legislature has until Saturday to vote on AB 566.