On April 9, 1945, Lutheran theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer was executed by the Nazis for his role in the plot to assassinate Hitler. Shortly before he died, he said: “This is the end — but for me it is the beginning of life.”

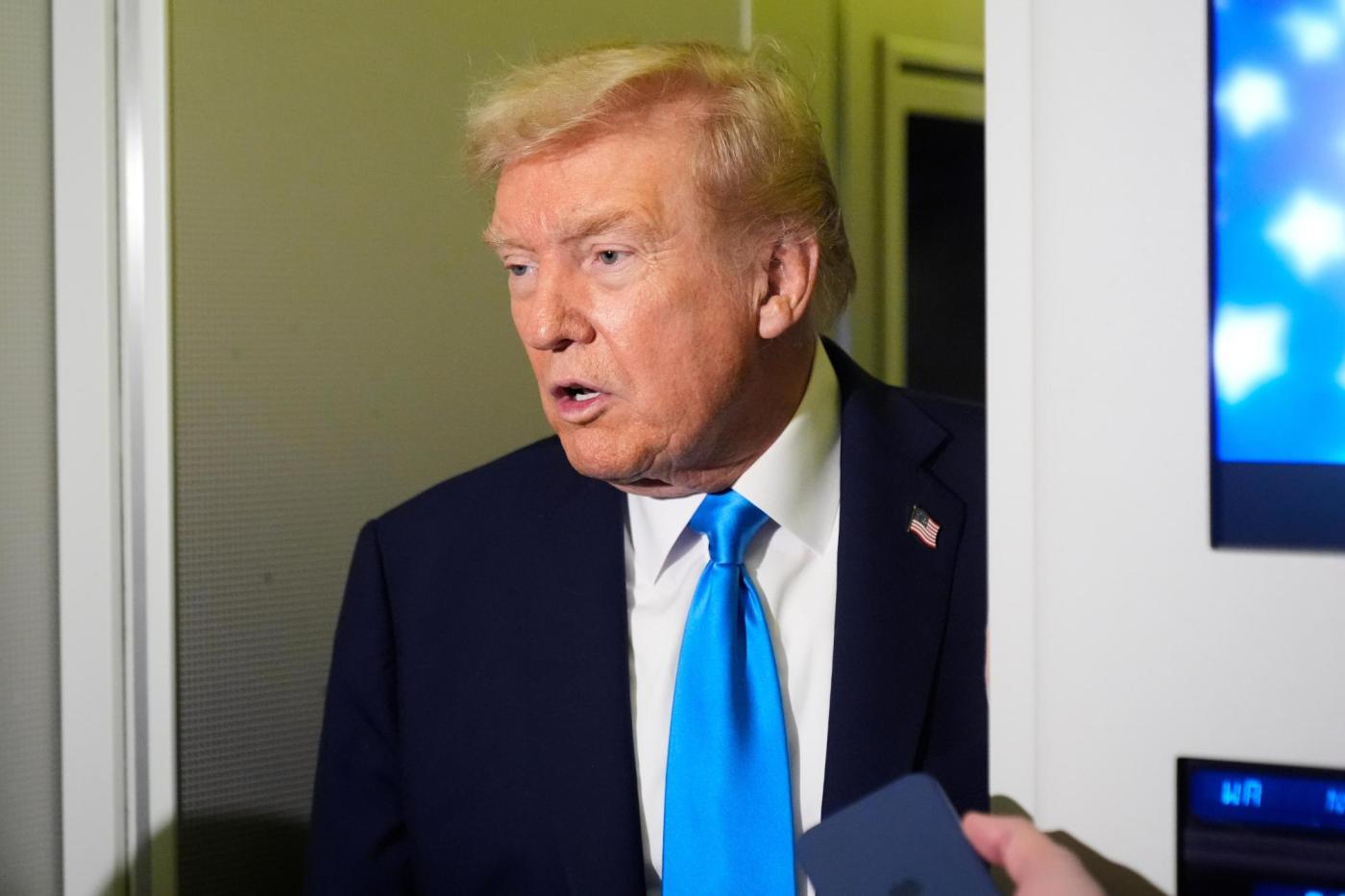

His example for our times is fraught with meaning. He opposed the “Fuhrer principle” that claimed the authority of a leader’s words stood above all law and policy and commanded absolute obedience. We’re not there yet but the bizarre deference to Trump’s rhetoric and his extreme claims of executive authority evoke comparisons to that earlier authoritarian era.

Bonhoeffer also opposed any easy alliance of Christianity and the state. On behalf of Christian denominations, he signed the 1934 Barmen Declaration that rejected the German Christian movement allied with the Nazi regime. We’re not there yet either but the increasingly seamless identity between right-wing Christians and the Trump federal government are steps on the road toward that problematic past.

But I would like especially to note a dimension of Bonhoeffer’s thought of which he himself was a magnificent example: conscience.

David DeCosse (Santa Clara University)

In the last years in the United States, the idea of conscience has been taken over by conservative religion: If conscience has become a public issue, it’s because it’s had to do with a baker or a nurse or a county clerk who has a religiously informed conscience that objects to participation in a practice that involves some departure from traditional norms pertaining to contraception, same sex marriage, or abortion.

But Bonhoeffer offers a wider and better view of conscience that can help us navigate our present moment of a politics of lies. First, his own personal witness stands forever as an example of word and deed united in the face of the greatest danger: He gave his life for what he believed in the face of a regime dedicated to murder.

Second, he noted how an ethics of conscience could get lost amid the thousand daily compromises that the Nazi regime forced on a person. Persons easily deceived themselves and failed to realize that a bad conscience (“I have done wrong and I know it”) may be better than a deluded one (“I must compromise with this evil for the sake of the good”).

Third, he argued that a commitment to a righteous conscience could be a subtle form of escape. I can uphold the moral law and do the right thing and fail to take responsibility for a disaster unfolding all around me because I’m so concerned for my own moral purity.

Finally, he argued that the origin and goal of conscience was the living presence of God in the world and in one’s neighbors. In making such a claim, Bonhoeffer moved the aim of conscience away from obedience to rational principles and to the more demanding and concrete love for God and one’s living, breathing, suffering neighbor. Indeed, he said that we should take “the view from below,” as he put it, and consider those neighbors who are especially bearing the brunt of injustice and who live in worlds marked by evil and failure and compromise. Love must prove itself there.

Related Articles

Stephens: Donald Trump’s wanton destruction of the American ideal

Oakland mayoral race: Loren Taylor’s backers outspending Barbara Lee’s support in final days

San Pablo leaders set multi-year vision for city

Brentwood on the lookout for new city manager

Gessen: Unmarked vans. Secret lists. Public denunciations. Our police state has arrived.

Bonhoeffer’s understanding of conscience inspires heroic action: People really can do the most dangerous and noble things — a good reminder in our low, dishonest times.

And Bonhoeffer’s understanding of conscience is inspired by religion not to protect religion but to turn religion in service to the concrete, suffering world in which Christ is present in all.

The leadership principle; Christian nationalism; lies and criminalized stereotypes of vulnerable populations: Bonhoeffer rejected all of it and challenged the conscience of any Christian who found a home in that world. In case we aren’t persuaded by his words about such matters, we can take the opportunity today to reflect on the even more persuasive power of his death.

David DeCosse is the director of religious and Catholic ethics at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University.