Ever since Maria Puga saw the cellphone footage nearly 15 years ago of her husband crying out in anguish while on the ground encircled by federal border officers, she has known that he was tortured before he died, she said Thursday.

This week, in a first-of-its-kind decision, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights agreed, finding that federal law enforcement officers tortured Anastasio Hernández Rojas by beating him with batons, Tasering him multiple times and kneeling on him while he was handcuffed at the San Ysidro Port of Entry.

The landmark decision marked the first time the commission, an international body that’s part of the Organization of American States and investigates massacres, extrajudicial killings and other rights violations across the Western Hemisphere, has issued such findings in a case concerning a death at the hands of U.S. law enforcement.

The commission also found federal officials conducted a biased and incomplete investigation of Hernández Rojas’ death, used excessive force while he was restrained, discriminated against him and denied his family justice, all in violation of international protocols to which the U.S. has agreed.

“The acts of police violence against Mr. Hernández at the San Ysidro Port of Entry were perpetrated intentionally, with the aim of intimidating, controlling and punishing, and … caused intense suffering to the victim, and (the commission) concludes that they constituted acts of torture,” the commissioners wrote in the 43-page report released Wednesday.

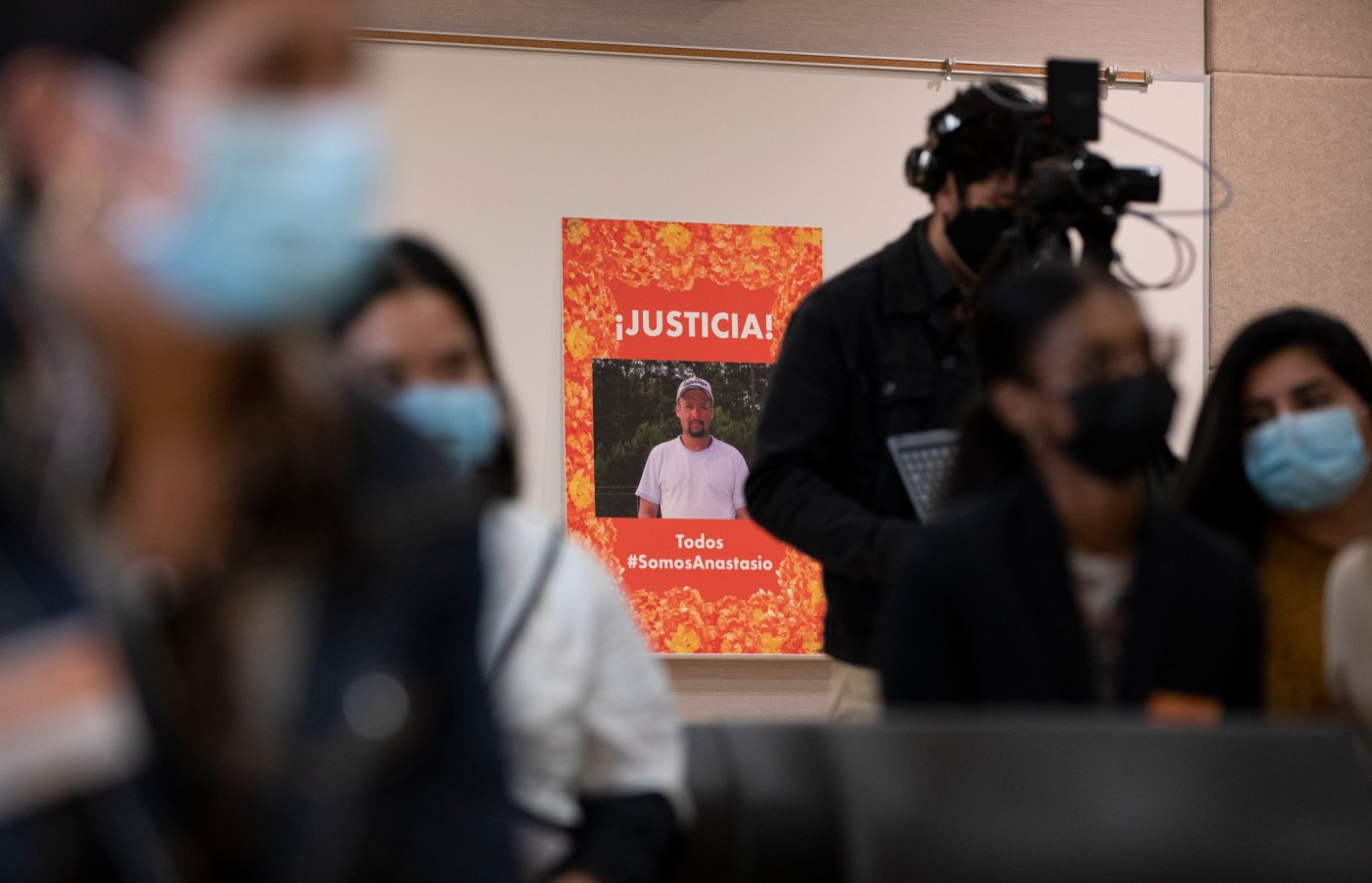

Maria Puga, the widow of Anastasio Hernandez Rojas, participates in a hearing with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights about the death of her husband on Nov. 4, 2022, in San Diego. (Ana Ramirez / U-T file)

“This is the truth,” Puga told the Union-Tribune on Thursday. Speaking in Spanish, she said her husband’s death destroyed her and the couple’s five children, but hearing his cries sparked a mixture of courage and rage that has pushed her for more than a decade to seek justice. She said she hopes the U.S. will follow the commission’s recommendations to reopen the investigation and hold accountable the officers responsible.

Related Articles

Man arrested on suspicion of smuggling exotic parakeets inside cowboy boots across California-Mexico border

Trump’s nominee for CBP commissioner faces questions about role in California-Mexico border death investigation

Judge restricts Border Patrol in California: ‘You just can’t walk up to people with brown skin’

California judge blocks Trump administration anti-money laundering affecting border businesses

Man sentenced for illegally trafficking baby spider monkeys across California-Mexico border

“(This is) the first time an independent, impartial body has provided a full accounting of what happened to Anastasio,” said Roxanna Altholz, the director of the Human Rights Clinic at UC Berkeley Law and one of the attorneys who represented Puga and her family in the case along with Andrea Guerrero of Alliance San Diego. “(The commission) also made a landmark holding — that the cornerstone of U.S. law on use-of-force, the so-called ‘objectively reasonable’ standard, violates international human rights law.”

Altholz said the commission’s decision “is more than a condemnation,” but rather “a blueprint for structural reform and a call for the U.S. government to align its laws and policies with basic principles of human rights and dignity.”

Hernández Rojas, who was 42 when he died, was a Mexican citizen who had lived in San Diego since he was a teenager. Shortly after being deported in May 2010, he was detained while trying to sneak back into the country and taken to the San Ysidro Port of Entry, where he was to be sent back to Mexico. Authorities have said he was confrontational and that at one point he allegedly tried to kick federal law enforcement officials. During the incident, two Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents hit him with batons and another agent kneeled on his back. A Customs and Border Protection officer fired a Taser at him four times while others held him face down.

Hernández Rojas stopped breathing during the encounter and was hospitalized for about two days before being taken off a ventilation machine. An autopsy by the San Diego County Medical Examiner’s Office ruled his death a homicide and found numerous factors contributed to a fatal heart attack, including methamphetamine intoxication, heart disease, the Taser shocks, the physical exertion and restraints. That autopsy concluded the methamphetamine played a key role in his death, while a second, independent autopsy concluded the methamphetamine was not a key factor.

The FBI, the U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division, the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Inspector General and a grand jury all investigated the death. They concluded in November 2015 that no criminal charges would be brought against the officers involved. Hernández Rojas’ family sued the federal government, settling the civil suit in 2017 for $1 million.

But Puga continued pushing for justice and took the case to the human rights commission, which is a body within the Organization of American States and based in Washington, D.C.

The U.S. Department of State represents the U.S. in the Organization of American States. State Department officials repeatedly failed or declined to engage on the merits of the case, instead asking that the commission not take up the case because Hernández Rojas’ family had already settled its civil lawsuit. The U.S. also argued that agreements guaranteeing certain human rights signed by the international organization’s members are nonbinding, meaning the United States doesn’t have a legal obligation to follow them.

From left to right; Roxanna Altholz, Andrea Guerrero, Maria Puga, Gabriela Lanzas, and Rafael Barriga participate in a hearing with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights about the death of Anastasio Hernández Rojas on Nov. 4, 2022 in San Diego. (Ana Ramirez / U-T file)

The commission noted in its report that it gave the U.S. government the chance to respond to its findings in December and again in March. The commission said the government never responded.

Altholz, the attorney from UC Berkeley, criticized the U.S. in 2021 for its failure to respond, saying it would give “authoritarian regimes in the Americas permission to do the same.”

She said Thursday that she and the other attorneys in the case are “not naive. We know that the United States has a long history of rejecting international decisions against it. But we also know that Anastasio’s family are not alone. They are part of a growing movement of survivors, advocates and communities who believe that dignity does not stop at the border, and neither should justice.”

The case has already resulted in one concrete measure — the disbandment of so-called Critical Incident Teams that operated without oversight in Border Patrol sectors along the U.S.-Mexico border. The secretive units, the first of which was created in 1987 in the San Diego Sector, inserted themselves into investigations of incidents they did not have authority to investigate, according to a report last year by the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

Guerrero from Alliance San Diego and other attorneys investigating Hernández Rojas’ death alerted Congress about what they called the “shadow police units” after finding indications that the unit based in San Diego had tampered with and even destroyed evidence in Hernández Rojas’ case to protect the agents involved. They then began finding documentation of other cases in which similar units had interfered in other sectors.

Among their findings was that President Donald Trump’s pending nominee to lead CBP, Rodney Scott, signed an administrative subpoena for Hernández Rojas’ medical records that the attorneys claim were then withheld from San Diego police officers investigating the death. Scott, who was the acting deputy chief patrol agent in San Diego at the time, was questioned about his role in the Hernández Rojas case on Wednesday during a confirmation hearing in front of the Senate Finance Committee.

Two former high-ranking CBP officials submitted affidavits in the human rights commission case. One stated that kind of use of an administrative subpoena was “illegal and potentially obstruction of justice.” Another called its use “improper if not criminal.”

Scott acknowledged Wednesday that he signed the subpoena but testified that it was a standard procedural act that he completed after the subpoena was reviewed by legal counsel. Asked if he’d interfered in the investigation of Hernández Rojas’ death, he answered “absolutely not.”